The projects and global community that came to fruition through the Sisters Against Violent Extremism (SAVE) network since 2008, reinforced Women without Borders’ (WwB) understanding that mothers in particular have for too long been excluded from prevention strategies. In an effort to grasp why mothers did not figure prominently and to explore the notion of Mothers Preventing Violent Extremism (MPVE), WwB conducted the first in-depth applied research study centred on mothers and security, entitled ‘Can mothers challenge extremism?’. As part of the SAVE network ‘Mothers for Change’ campaign, WwB observed 1023 mothers’ attitudes towards, perceptions of, and experiences with radicalisation and violent extremism in their families and communities in Pakistan, Palestine, Israel, Nigeria, and Northern Ireland. The research revealed that although mothers are best suited and situated to recognise and react to early warning signs of radicalisation due to their place at the heart of the family, often they lack the appropriate space, structures, and training to develop the necessary competence and confidence to assume their prevention role. On the basis of the study findings, WwB conceptualised and developed the pioneering and globally-recognised ‘MotherSchools: Parenting for Peace’ Model.

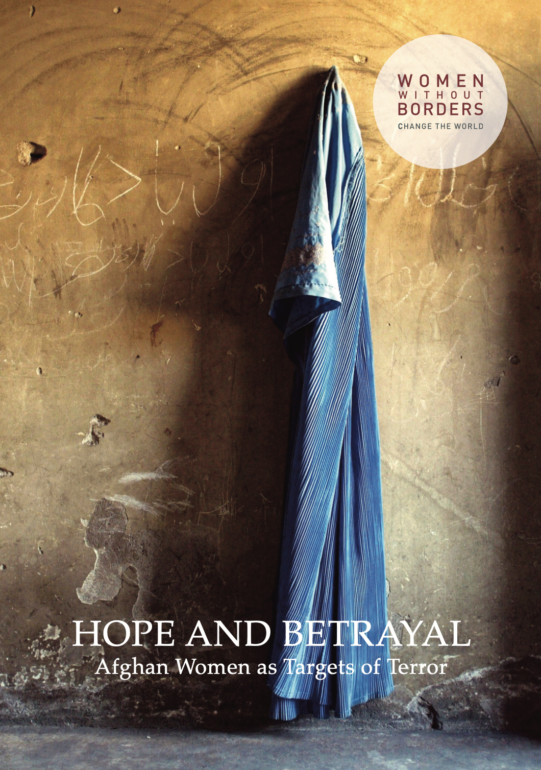

While acts of terrorism repeatedly bring to the fore complex questions of ‘why’ and ‘how’ young people are radicalised, attempts at profiling extremists and terrorist groups have fallen short of viable universal explanations. Scholarship on the subject increasingly acknowledges the limits of global profiles that purport to depict ‘the ordinary terrorist’ and now generally arrives at a common conclusion: the sources and appeals of extremism vary over time and space, tend to transcend socio-economic and political factors impacting on an individual, and overwhelmingly originate from and develop out of local, context-specific circumstance. Considerations of and responses to radicalisation in particular should thus study and reflect how the process emerges at the individual level and progresses to affect the local, national, and global levels. Yet in the problem’s transition and spread from the micro to the macro, there is one preventative, universal agent whose potential and agency overwhelmingly has been overlooked: the mother.

The projects and global community that came to fruition through the Sisters Against Violent Extremism (SAVE) network of projects and grassroots activists since 2008 reinforced Women without Borders’ (WwB) understanding that mothers in particular have for too long been excluded from prevention strategies. In an effort to grasp why mothers did not figure prominently and to explore the notion and potential of Mothers Preventing Violent Extremism (MPVE), WwB Founder and Executive Director Dr. Edit Schlaffer and WwB Research Director Professor Ulrich Kropiunigg conducted the first in-depth applied research study on mothers’ potential in the security arena, entitled ‘Can mothers challenge extremism?’. Supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and a part of the WwB SAVE network ‘Mothers for Change’ campaign, this three-year study captured 1023 mothers’ attitudes towards, perceptions of, and experiences with radicalisation and violent extremism in their families and communities in Pakistan, Palestine, Israel, Nigeria, and Northern Ireland.

The three-stage research study was designed to collect, analyse, and apply data from mothers living in regions affected by violent extremism. The first two hundred in-depth interviews that WwB conducted provided a comprehensive understanding of the social and emotional environments of adolescent and young adults across all five countries. The questions were grouped into seven areas: family background, the children’s lives, a mother’s role in her child’s upbringing, proximity to extremism, societal factors in contexts impacted by violence in particular, existing coping mechanisms for violent extremism individually and collectively, and future strategies.

In many communities, extremism and violence are taboo; therefore, gathering data requires breaking through social barriers. Some women were reluctant to talk at first, particularly mothers whose children were already involved in extremist activities. Guilt, shame, and fear initially inhibited them. They eventually opened up once they understood that they are valuable contributors and allies. Many subjects expressed relief after speaking out. From these interviews a number of themes emerged, and these were used to develop a questionnaire. Three key areas were explored. First, how mothers view their role in reducing the attraction of extremist ideologies. Second, whom they would turn to in a situation characterised by confusion, fear and alarm. Third, what they require in order to effectively recognise and respond to the warning signs of radicalisation.

The questionnaire used a Likert scale to capture levels of agreement across forty-three statements and questions. The data from both the interviews and the surveys conveyed the collective concern among mothers that their children could become radicalised. Most mothers were confident in their own ability to prevent their children from involving themselves in violent extremism, and to recognise early warning signs. A high number of mothers expressed a sense of urgency and eagerness to collaborate with similarly concerned mothers in order to combat recruitment.

The study asked two central questions: ‘Where do mothers turn when they have concerns about their children’s safety and well-being?’; and ‘What people or institutions do they trust to provide support?’ At 94 per cent, the research suggested that mothers trust other mothers above anyone else. Fathers came a close second at 91 per cent, followed by other relatives at 81 per cent. Teachers ranked fourth with a trust score of 79 per cent, and community organisations, at 61 percent, are the first institutions the mothers turn to outside of immediate social networks. Religious leaders earned a 58 per cent trust score, pointing to a level of ambivalence. State institutions received one of the lowest scores, with police at 39 per cent, the army at 35 per cent, and local government at 34 per cent. International organisations earned similarly low trust scores at 36 per cent. The government, however, earned the lowest trust score: 29 per cent. That mothers trust in themselves and other mothers first and foremost amounts to an important finding in the light of the fact that existing security approaches have tended to focus on solutions that involve two greatly distrusted groups: national and local authorities.

The interview and survey data points to high levels of concern regarding radicalisation. Some 86 per cent of mothers viewed increasing their knowledge of the warning signs the greatest priority, closely followed by training in self-confidence, parenting skills, and computer literacy. The majority of mothers wished to connect with other concerned mothers, and to speak out together against extremism as a united front. Mothers thus are confident in their own security potential if equipped with the right tools and knowledge. While a strong awareness of their needs indicates that they already are addressing radical influences, they nevertheless feel that their responses are less than adequate.

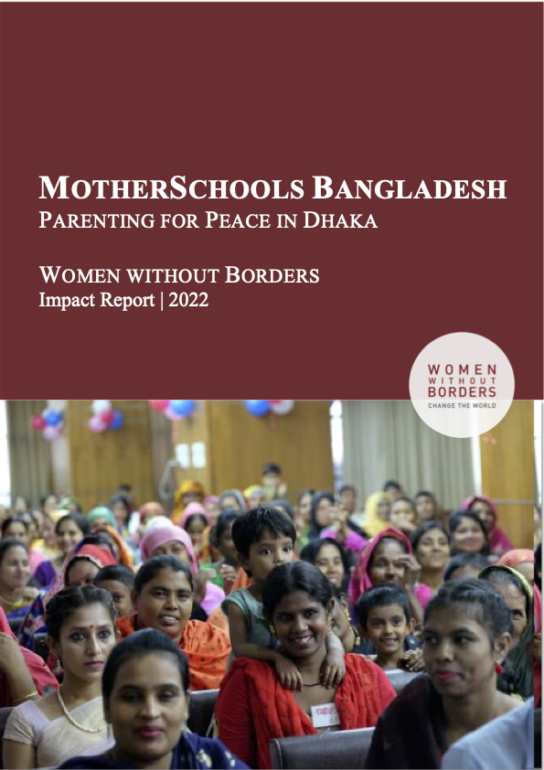

Drawing on the results of its ‘Can Mothers Challenge Extremism’ research, Women without Borders applied the findings by developing the comprehensive ‘MotherSchools: Parenting for Peace’ Model to a) address the needs and grievances of the 1023 participants from the study, and b) harness the untapped potential of mothers in preventing violent extremism by c) building up their skills and self-confidence in parenting, and c) strengthening resilience in their homes and communities.

In translating the research findings into action, WwB’s MotherSchools programmes have since 2013 managed to identify, unlock, and activate the potential of mothers across twelve. As popular strategies like counter-narrative approaches disseminated over the internet repeatedly have fallen short of catching up with recruitment tactics, this grassroots approach has emerged as a good practice that has contributed to rethinking and reshaping P/CVE policy worldwide.